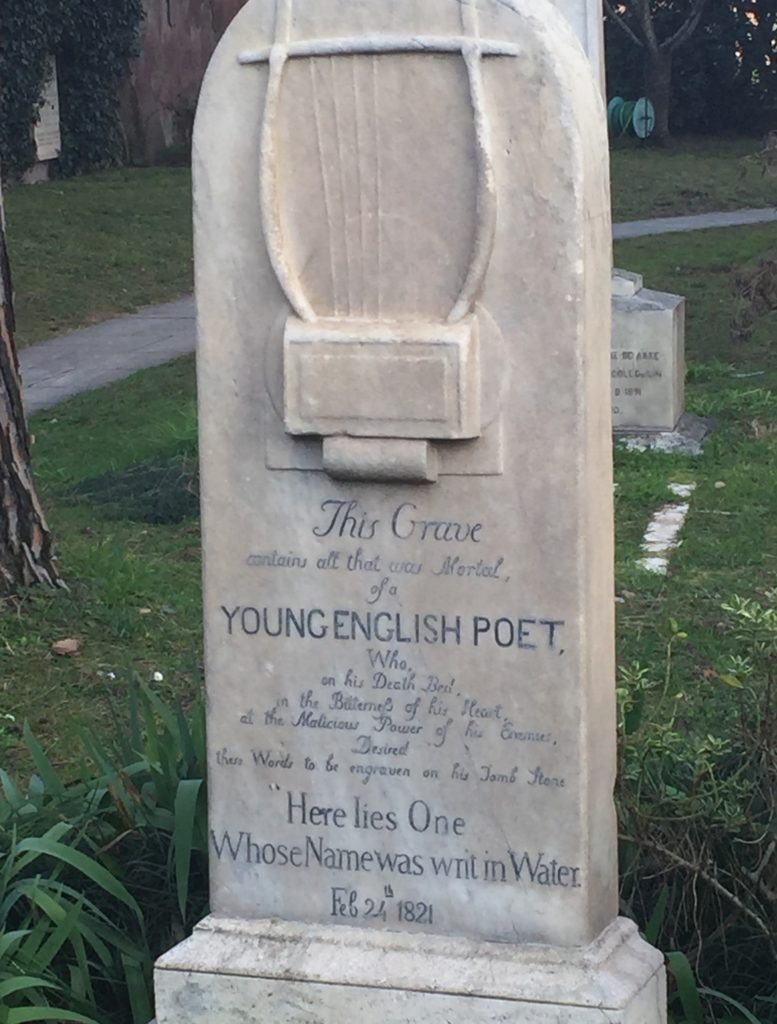

“This grave contains all that was Mortal of a Young English Poet Who on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart at the Malicious Power of his Enemies Desired these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone: Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. 24 February 1821.”

These are the words engraved upon the tombstone of John Keats, marking the final resting place of the famous English Romantic poet. The stone is quaint compared to many of the others decorating Rome’s Protestant Cemetery (known to some as the Englishman’s or Non-Catholic Cemetery). Many are buried within the cemetery’s quiet walls, some are more well-known than others. Writer Percy Shelley also rests here, as well as Antonio Gramsci and August von Goethe. Beside the site stands the Pyramid of Caius Cestius, a massive monument faced in marble and constructed sometime between 18 and 12 BC.

Even before entering the Protestant Cemetery, the beauty held inside is made apparent by its gated archway. Small trees growing on either side of the arch dutifully stand at attention, their waxy green leaves contrasting the solemn gray walls. A gold-and-blue seal on the gate creates further contrast, glowing ever so slightly in the late afternoon sun. Upon entry, a pale cream-colored sign directs visitors to the cemetery’s most notable graves. No fewer than ten steps in, it is impossible to ignore the fauna—trees, bushes, and plants of all varieties–that surround each grave. Their beauty is warm and welcoming, especially to those whose lost ones may be buried below.

Once inside, it is only a matter of time before visitors encounter a cat. The cats are strays, feed and taken care of by volunteers. The Protestant Cemetery is their home—behind its walls, they can roam freely without fear of danger or death. The strays have found a place to live among the dead, guarding their graves and their souls from any evil spirits (living or nonliving) intending to do them harm. The cats are friendly and used to visitors, often allowing themselves to get pet by passersby.

Walking between rows of graves, the sheer number of tombstones can be startling. They are everywhere—sometimes separated by less than a foot. Each stone is unique in either construction, language, or religion. Approximately 15 languages are represented among the entire collection, lamenting the deaths or celebrating the lives of artists, politicians, knights, leaders, and writers.

As I begin to write, I stand beside the grave of John Keats. There is something powerful about this place—something ancient and awe-striking. Something that caused author Oscar Wilde to throw himself down beside the tombstone and write a poem out of reverence for what he had encountered (“The Grave of Keats”). Something that draws regular visitors and channels its energy into the beautiful greenery and abandoned felines. Something that courses through my veins as my pen meets the page.

In the words of Isaac Newton: here, I am truly standing on the shoulders of giants. Rest peacefully, Keats.